What Actually Is Education? A Journey Through the Past

Welcome to our new exhibition titled "What is Education? Education and Training since Antiquity." In this exhibition, we explore the question of what education is actually meant to achieve. Is it about acquiring knowledge, or should education aim to create the ideal person? Using books from the MoneyMuseum's collection, we illustrate different educational ideals and approaches, from antiquity to the 19th century.

To the Stops

by

Ursula Kampmann

The German word for ‘education’ is ‘Bildung’, which comes from the Old High German word ‘bilidunga’, meaning image or reflection. This takes us back to where education began, namely in the family: every child lived with their clan and helped where they could. They learned what they needed to know through imitation. This form of education probably dates back to the beginning of human history. It would have begun with the development of language, which made it possible for the older generation to orally pass on their own experience to the younger generation.

Then came writing, and from that point on, education was no longer about what we learned from our parents, but what we learned from books. Books allow us to draw on the knowledge of all people who have written down their experiences. This gives us access to an enormous treasure trove of knowledge, which even in ancient times was considered far more valuable than anything we could learn by imitation.

But this posed a new problem: the number of skills taught in written texts is infinite. Which ones does a person need to master in order to succeed in life? This question is answered a little differently in every society and period of history, leading to what is known as the ‘educational canon’.

But is education really just about acquiring knowledge? The philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment took a different view. They called for an education that would enable everyone to lead a happy life in harmony with their fellow human beings.

The new exhibition at the MoneyMuseum in Zurich focusses on what we today refer to as education. We use books to illustrate different educational ideals.

The first part of the exhibition looks at the past – from antiquity to the 19th century. First, we stop off at the Greeks and Romans; then, we progress to the Middle Ages to examine how the educational ideals of a knight differed from those of a cleric; we go to the beginning of the early modern era to understand how the monetary economy and the Reformation changed our education system; and finally, we look at the Age of Enlightenment, when the middle classes began to dream that education could create the perfect human being. As many people wanted to do without God and the church from then on, it was in the hands of man to realize paradise on earth.

The second part of the exhibition revolves around the present and the future. Using the example of economic education, we illustrate the extent to which the educational canon taught at universities no longer corresponds to our reality, and discuss the new approaches we could take to adapt economic education to our requirements.

Station 1 - Antiquity: Rhetoric, Philosophy and Critical Thinking

Our education is rooted in antiquity. Many of the academic disciplines we teach and learn today were first developed in Athens and Rome. Latin and Greek, mathematics, music and sport have been on the curriculum for around 2,000 years.

The first book we’re presenting to you is called Politeia or Republic, written by Plato. In it, he calls for a person's function within the community to be determined by their intellectual capacity and education. He wanted there to be less emphasis placed on factual knowledge and more on unselfish action, independent thinking and an infallible moral compass.

Since then, many statesmen have claimed to live up to this ideal. One of them was Cicero, one of the leading politicians at the time of the fall of the Roman Republic. His rhetorical skills propelled him to the top of the Roman Senate. We’ll also present his rhetorical writings, which taught thousands of theologians and statesmen to present their causes as the only morally justifiable ones.

1.1 – Plato’s State: How To Educate One’s Rulers

The Downfall of Athenian Democracy

When Plato was born in Athens in 428/7, the Athenians were proud of their democracy. Every full citizen had the equal right to participate in political decisions, though women, slaves and those without citizenship were of course not considered full citizens. In order to ensure equal opportunities among the privileged Athenians, all political appointments were drawn by lot and allowances were paid out.

The system was financed by Athens' allies, whose contributions to the Delian League were being misappropriated for that. Eventually they refused to put up with this any longer and, shortly before Plato was born, the Peloponnesian War broke out. Much to their surprise, the Athenians suffered a crushing defeat. Plato was 24 years old at the time of the peace treaty. He would have joined other citizens at the agora to discuss the reasons for Athens’ failure. In his books, he propagates a new morality: he contrasts human self-interest, which led to Athens’ downfall, with the pursuit of the Good.

While Plato was writing his book on the ideal state, Athens’ heyday was over. Plato died in 348/7, ten years before the Battle of Chaeronea, which sealed Athens’ fall into political insignificance.

Plato

Plato came from one of the richest and most distinguished families in Athens, which had already brought forth many important politicians. He therefore had an excellent education. His basic education in reading, writing, arithmetic, ritual dances and music was provided by private tutors. At the age of 14, Plato entered the state-funded gymnasium. There, like everyone else, he underwent physical training to prepare him for military service. He also had some intellectual training in the form of occasional lectures and reading. Each gymnasium had a library.

Plato did not have to work after completing his training. Instead, he joined the followers of the philosopher Socrates. He listened to his discussions and learned from them. It is difficult to overestimate the influence that Socrates had on Plato. However, we do not know exactly what form this influence took. Socrates left no writings behind. Everything we think we know about Socrates has been handed down to us by his students. It is therefore difficult to pinpoint where Socrates’ teachings end and the interpretations begin. The Republic also purports to describe a discussion that Socrates held during a banquet.

The Origins of the Republic

In 399 BC, the Athenian court sentenced Socrates to death for impiety. Plato was deeply affected by this. He left Athens and travelled through the Greek world. During his travels, he came into contact with the Pythagorean philosophers in southern Italy, who already had their own schools. Following their example, Plato founded his own school, the Academy, after his return around 387 BC. There, he taught his students what he believed really matters when it comes to human coexistence.

The Republic is the core of Plato’s legacy. Written around 375 BC, it describes the ideal society. He calls it ‘Kallipolis’, meaning ‘beautiful city’, because the ideal of beauty and goodness is perfectly realized within it.

In the Republic, Plato rejects the radical democracy of Athens. He contrasts the equality of all citizens with a class society in which class is defined by the ability to think.

- Those who have only mastered basic education serve as farmers and craftsmen. They live in family groups, own private property, but have no influence on the government.

- Those who are distinguished by their courage during training become Guardians: they protect the community against internal and external enemies as policemen and soldiers.

- Those who demonstrate particular intellectual ability become members of the government at the age of 50.

Citizens of the Kallipolis – including women! – have the same opportunities for a good education. They are bred specifically to produce particularly gifted children. All babies are separated from their mothers immediately after birth and handed over to be raised by the state. People who are mentally or physically impaired are abandoned and thus indirectly killed.

Plato rejected traditional Greek education, in which the memorisation of the great epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey played a central role. He considered the myths to be immoral and unsuitable as parables.

Instead, he advocated education through music, which he believed penetrates deep into the soul and promotes beauty. Plato’s love of music inspired the legend that he was a son of Apollo.

After completing basic training, citizens are sorted into classes. Those who have not distinguished themselves are assigned the class of farmer or craftsman. The others learn meekness towards citizens and bravery towards enemies in order to qualify as Guardians.

In Plato’s ideal state, only the exceptionally gifted are trained in arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and harmony. These lessons serve to sharpen the mind. At the age of 20, young men are taught philosophy in order to learn to strive for the good and the beautiful. They must perform many years of service in the community before they can assume public office at the age of 50.

Plato’s ideas have influenced us greatly. If we believe today that the best leaders are motivated not by selfish but by altruistic reasons, it is because we have adopted Plato’s idea of the ‘philosopher king’.

1.2 - Cicero: Learning How to Form and Control Opinion

The Roman Timocracy

When Cicero was appointed to the Senate in 74 BC, there were around 600 senators in charge of the fate of the Roman Republic. Anyone who wanted to push through their political views had to convince these 600 men. If – like Cicero – they had no family alliances, they would instead have to score points through their personal demeanour. How one spoke, argued and refuted counter-arguments played a decisive role.

Only very few Roman citizens could afford to provide their children with a good enough education to give them a chance in the Senate. That suited the system well. The Roman Republic was not a democracy, but a timocracy, a state in which a citizen’s wealth mattered above all else.

Cicero

Cicero came from a wealthy and well-connected family, which meant he had an excellent education. He was taught how to read and write, and also learned Greek, not at one of the public schools, but at home, probably from a Greek slave bought especially for this purpose. Greek was essential for accessing higher education, since all the important textbooks were written in this language. Cicero was one of the first authors of Latin textbooks.

Where and what a young man learned after his basic education depended heavily on his family’s connections: Cicero’s aunt was related to a friend of the most famous orator of his time, and so Cicero became his apprentice: he accompanied him, listened to his speeches and helped with the preparations. He then received similar training from a lawyer who was very well known at the time. Cicero then went to Athens and Rome, where he studied philosophy. He completed his education in 75 BC, when he was old enough to enter politics.

Cicero’s Rhetorical Writings

Cicero was very successful because of his rhetorical skills. He became famous when he drove the former governor of Sicily, Gaius Verres, into voluntary exile in 70 BC. The speech he gave on that occasion is still taught in schools today, as are those denouncing Catiline.

This is also due to the fact that Cicero meticulously published all his speeches during his lifetime and used them as examples in his rhetorical writings. We still have the full or partial originals text of 58(!) speeches today. We also know the titles of a further 100 speeches.

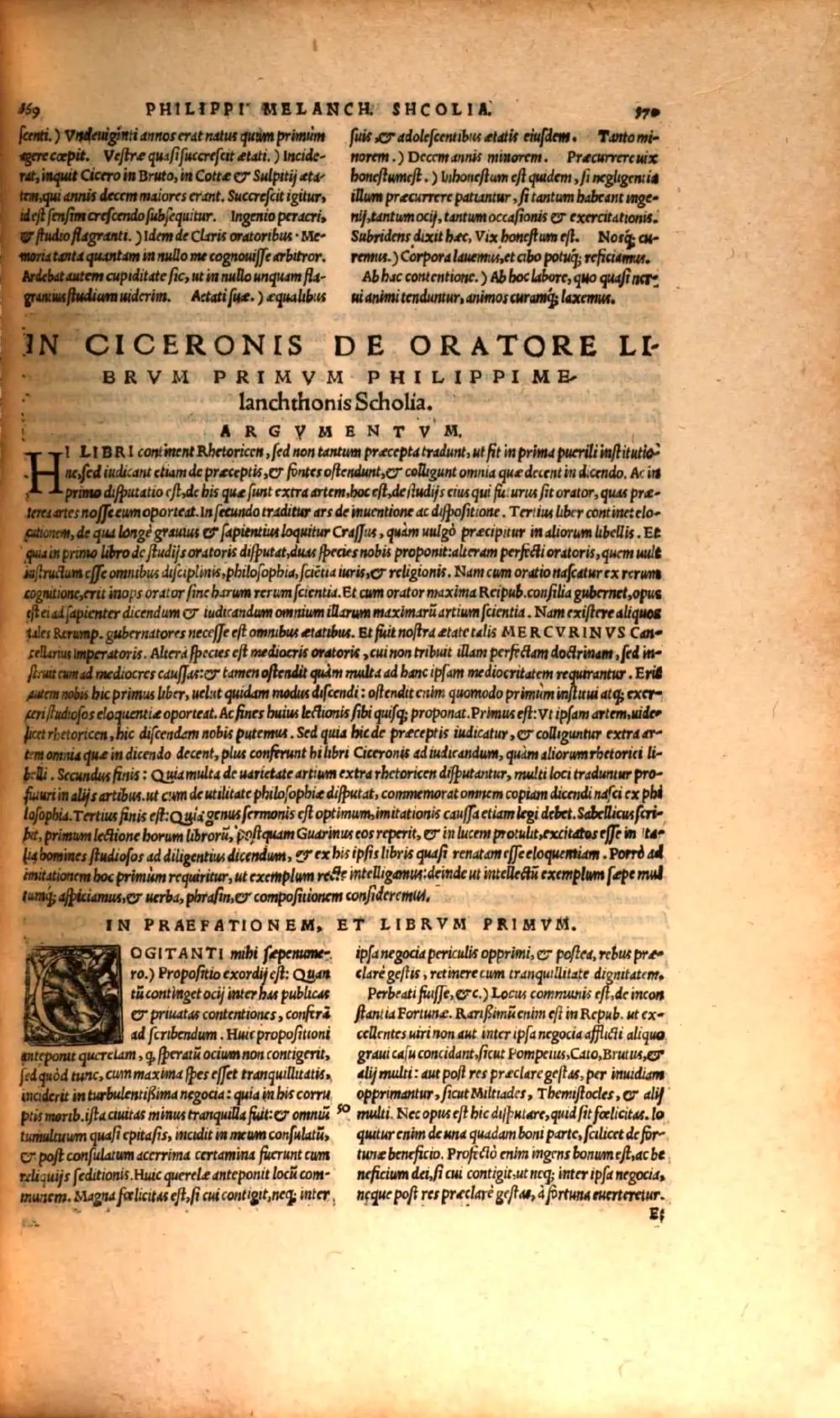

The humanists considered Cicero to be the most important Roman author. He satisfied their need for ‘Classical’ Latin, which differed from Ecclesiastical Latin. The humanists used Cicero’s writings to relearn the Latin language, which is why they collected his rhetorical writings and published them again and again. Our print dates back to 1541 and was produced in a Basel printing house run by the prominent humanist Thomas Platter. He also commissioned the French philologist Jacques-Louis Strebée, who added the most important scholarly commentaries by other humanists to Cicero’s works.

At the time of the Renaissance, Cicero’s main work, De Oratore, written around 55 BC, was held in the highest esteem. This is why it appears at the beginning of the book. The title means ‘On the Orator’ and the book does indeed contain everything one needs to know in order to craft an eloquent speech: the requirements an orator must meet; the training they need; how they should structure their speech and the style they should choose. Following in the footsteps of Plato, De Oratore is structured as a dialogue.

In De Oratore, Cicero adopts Plato’s idea that politicians must be trained in philosophy, as this enables them to expose the true enemies of the community. A good statesman does not pursue his own interests, but those of Rome. Cicero was alluding to the politics of the day: he presented himself as an unselfish politician in contrast to Caesar, who was concerned about his rank. However, we might question this image today. Cicero’s ‘Rome’ consisted of a tiny, corrupt, incompetent, arrogant and egotistical upper class. The citizens’ misery was of no interest to any of the senators who, with their uncompromising attitude, drove Caesar to cross the Rubicon on 10 January, 49 BC and thus trigger the civil war.

Strebée helped readers by publishing not only Cicero’s actual text but also scholarly commentaries by other humanists. One of them was the Lutheran reformer Philipp Melanchthon. This gives us a small clue as to why Cicero’s oratory was so popular in the 16th century: Cicero taught theologians how to remain victorious in arguments.

The anthology also contains Cicero’s earliest work on the art of oratory. It was written around 85 BC and is entitled In Rhetoricos de Inventione. We now know that Cicero excerpted parts of this from an older work, in some instances copying it word for word. This is proven by another work on the art of oratory that was not written by Cicero – Pro Rhetoricis ad C. Herennium (meaning ‘Rhetoric, for C. Herennius’), which also includes passages that can be found Cicero’s work as well.

Pro Rhetoricis ad C. Herennium is, incidentally, the oldest textbook on rhetoric in Latin that has been preserved in its entirety.

We know that Cicero did not prevail in the battle for Rome. After Caesar’s assassination, he delivered 14 urgent speeches, the ‘Philippicae’, to convince the Senate to resist Marcus Antonius. However, the latter did not rely on political speeches, but on soldiers: he had Cicero assassinated with Augustus’ consent on 7 December, 43 BC.

Station 2 - The Middle Ages: Education in a Society of Estates

In Europe, the end of antiquity brought the end of urban centres and, with it, the end of classical education. In the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic metropolises, education tied in seamlessly with ancient heritage; but in Europe, the tradition of preserving knowledge in writing only survived in the libraries of the few monastic and cathedral schools.

This situation did not change until after the turn of the millennium, when the ideals of the Church permeated all of society. As a result, there was increased respect for learning from books. The first universities were established.

Station 2 is dedicated to the exciting epoch of the late High Middle Ages, when the effects of these changes became apparent. The first part of Station 2 focuses on the central work of the most famous cleric of the Middle Ages: Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica became the most important textbook for students of theology.

The second part of Station 2 focuses on the Codex Manesse, which, with its many portraits, illustrates the skills that ideal Christian knights had to master.

The Role of the Church in the Middle Ages

The first estate prays, the second protects, the third works: this concept runs through all the thinking of the High Middle Ages, even if the reality was not quite as simplistic as the three- estate model would have us believe. Initially, the clergy were closely interwoven with the nobility, as many fathers would send some of their children to monasteries and chapters in order to avoid splitting up the inheritance.

But in the 10th century, criticism of this practice began to emerge at the monastery of Cluny: instead of a Church that was dependent on and ruled by the nobility, the reformers hoped for a Church in which the gospel would be the standard for action.

There were two points of contention at the centre of the debate:

- Should all clergy be personally poor?

- Should there be a cost associated with taking on a role in the Church?

Reform orders such as the Franciscans or the Dominicans no longer valued a clergyman for his lineage, but rather for his piety and achievements. They opened up their hierarchy and made it possible for educated brothers and sisters to ascend through the ranks. This gave a whole new meaning to theological education.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas was born around 1225 as the seventh child of an Italian nobleman. At the age of five, he went to the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, where his uncle was the abbot. Thanks to his uncle’s protection, little Thomas’s rise in the church hierarchy was guaranteed. Thomas received the best education possible at the time. It consisted mainly of rote learning. Even the youngest children had to learn Latin – both written and spoken – from an early age. The rod was not spared. The children were only allowed to play or talk to each other on Sundays – and of course, even then, they were only permitted to speak in Latin and not in their mother tongue. Grammar, or the mastery of the Latin language, was the first stage of the trivium. This was followed by training in rhetoric, which did not involve speaking freely, but rather writing documents and letters. Gifted children and those with influential relatives were taught dialectics, the art of argumentation, which prepared them for university.

At the age of 14, Thomas enrolled at the University of Naples. There he studied the quadrivium, the four classical liberal arts: arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. It was also there that he met representatives of the newly founded Dominican Order. They fascinated him to such an extent Thomas Aquinas joined the Dominican Order himself, despite the vehement protest of his family.

The Summa Theologica

The Dominicans had made it their mission to deliver sermons in order to keep people from believing heretical opinions. To achieve this, the preachers had to be excellently trained. In the 13th century, the best theological education was offered by the University of Paris. That’s where Thomas was sent. He studied under Albertus Magnus, who applied the methods of Greek philosophy to theology. Thomas Aquinas further developed his teacher’s ideas. He sought to make all religious beliefs logically comprehensible. This is how he became the leading theologian of the Catholic Church. The Dominicans recognised his talent and provided him with everything he needed. We assume today that he employed three to four secretaries.

His most famous work was the Summa Theologica, written between 1265/6 and 1273. The title can be translated as the ‘Summary of theology’. In it, Thomas Aquinas systematically outlines all the theological teachings of the Catholic faith.

The idea of a compendium was not new. Other theologians before Thomas Aquinas had already written such works. But the Summa Theologica provided logical justifications for the tenets of the faith, thus making it easier for preachers to deal with those whom the Catholic Church called heretics.

Thomas Aquinas addressed the following topics:

· God

· Creation

· Man

· Teleology – or why God created man

· Christ

· Sacraments

The fact that Thomas Aquinas’ proofs for the existence of God are still taught in religious education classes at grammar schools today illustrates just how momentous his work was. The best-known is his ‘argument from motion’:

There is motion everywhere in the world. Everything that moves was set in motion by something or someone else at some point, i.e. nothing can move by itself. Consequently, the world in motion presupposes God as its original mover, who Himself was not moved, but initiated the first movement.

Thomas Aquinas died in 1274, and was canonised as early as 1323. His works spread throughout the Catholic world. Their importance is demonstrated by the fact that they were among the first works to be printed by the first European printing press in Mainz, along with the Bible. In 1567, Thomas Aquinas was given the title Doctor of the Church after the School of Salamanca, which was heavily influenced by the Dominicans, had established his writings as mandatory teaching material.

In 1879 – more than 600 years after its publication – Pope Leo XIII issued an encyclical declaring the Summa Theologica to be the basis for the training of all Catholic theologians. He himself initiated a new edition, known as the Editio Leonina.

This was followed by many other editions, including ours. The Summa Theologica exists in such large quantities because every theologian needs a copy in their library for reference at all times. Its significance remains undiminished to this day and was most recently reaffirmed by an encyclical issued by Pope John Paul II in 1998.

2.2 - The Manesse Manuscript: Learning Courtly Behaviour

Advancement in Courtly Society

Unlike the clergy, membership in the nobility was not based on an individual decision, but on birthright. In the High Middle Ages, anyone with noble ancestors belonged to the nobility. However, a nobleman had a certain amount of influence over whether and how high he rose within his class. Anyone who distinguished themselves in the service of a high lord could hope for a reward. This often took the form of the hand of a rich heiress, who would provide her husband with power and prestige through her property. Women were not actually allowed to make decisions, but occasionally they were able to assert their wishes nonetheless.

Many knights followed an unwritten code of conduct to please women. The more important the court, the more complicated this code became for the knights serving there. A man’s behaviour became just as much a status symbol as his weapons and clothing.

A Knightly Education

The knowledge a future knight needed could not be learned from books. Between the ages of seven and ten, he was sent to the court of a prince, befriended by his family, for an apprenticeship. The skills he was taught there were not standardised, but depended on the opportunities available. The initial aim was for the boy to practise with weapons, learn to ride and build up his strength. Once he reached the age of puberty, he was made a squire. In this role, he was with his master at all times – whether on the battlefield or on a diplomatic mission. In this way, he learned courtly behaviour, when and how to speak, how to dance and which skills were valued by princes and high-ranking ladies.

As soon as the young man reached adulthood, he received either a permanent position at his lord’s court or a basic set of weapons, with which he set out to seek his fortune.

The Codex Manesse

Countless stories tell of the heroic deeds of wandering knights. They formed part of the evening entertainment at every court, recited by experienced singers who also composed their own songs. The Codex Manesse presents the most notable poets and their verses in impressive miniatures. It is one of the most important cultural artefacts of the German Middle Ages and has had a lasting influence on our image of knighthood.

Unfortunately, little is known about the origin of the manuscript. It was only in the mid-18th century that Johann Jakob Bodmer drew a connection between the manuscript and the Zurich-based Manesse family. Bodmer claimed that Rüdiger II Manesse (d. 1304) and his son Johannes (d. 1297) were the authors of the manuscript and that they had worked with Johannes Hadlaub and other Zurich nobles to create it. This is possible; after all, many of the poets who appear in the manuscript come from the area of southern Germany and Switzerland. It is not proven, however.

The fact that Bodmer’s theory has become so established is due to the Swiss author Gottfried Keller. In 1876/7, he published a very successful novella about the origin of the Codex Manesse. In Hadlaub, he tells the completely fictitious life story of Johannes Hadlaub, in which Rüdiger Manesse appears as a collector of courtly love poetry.

A Chivalric Virtue in the Codex Manesse: Courage

The central significance of the Codex Manesse is that it gives us an insight into the set of values in the world of knighthood, i.e. it demonstrates what a knight’s training should ideally lead to. Courage was very highly valued. Tournaments played a central role as tests of courage.

A Christian Ideal: Charity

Christian knights were also expected to show charity to the poor and sick.

Courtly Behaviour

Dance was a central part of every festival. Well-educated knights were expected to have mastered the most important dances and to perform them elegantly – but not, of course, in full armour and chain mail, as depicted in this miniature.

Of course, we cannot present the original Codex Manesse in this exhibition. Instead, we are showing you a facsimile published by Insel Verlag publishing house in 1926. This makes it one of the first facsimiles in the modern sense. It was produced on the initiative of publishing director Anton Kippenberg who, during a difficult economic period, developed the concept of printing important German cultural artefacts in their original form. In 1922, he published Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which was a great commercial success. This was followed in 1924 by the Mass in B minor, and in 1926 by the Codex Manesse in a limited edition of 370 copies.

Station 3 - Education in the Early Modern Period: Everything the Absolute State Needs

The beginning of the early modern period is characterized by the increasing importance of money and the city. Wars were no longer fought with loyal knights, but with mercenaries, who needed to be paid in hard cash. From the 16th century onwards, a prince’s power therefore depended on whether he managed to keep his coffers full. In order to do so, princes needed a new breed of courtiers, whom we would now call civil servants or politicians. The professionalization of the administration opened up career opportunities for anyone with an economic or legal education. The princely administrations were located where the money was earned, in the city. This gave the middle classes a whole new level of significance.

The first part of Station 3 is dedicated to a book that illustrates the new skills expected of a prince in the 16th century. Its author, the successful politician Johann of Schwarzenberg, created a manual for modern political action with his congenial rewriting of Cicero’s De Officiis.

In the second part of Station 3, we’ll introduce you to the Basel Euclid, a work that represents the educational reform that emerged from the competition between the Reformed and Catholic educational institutions.

3.1 - A New Educational Ideal For a New Ruling Class

Competition at the Prince’s Court

No one can rule alone. That is why, for centuries, rulers have brought people into their council from whom they expected wise advice. In the Middle Ages, this was the task, duty and privilege of the feudal lords. This changed in the early modern period. Now, council members were not valued so much for their experience in warfare, and instead were expected to discuss monetary policy measures, the founding of cities, treaties and other topics that required experts with a university education.

As these posts were very lucrative, competition arose between the noble feudatories and the bourgeois scholars, whose education surpassed that of any nobleman. In the long term, this would lead to more and more noblemen attending universities and, conversely, more and more successful bourgeois experts being ennobled. The book we are presenting to you in the first part of Station 3 marks the beginning of this development.

Johann of Schwarzenberg

Johann of Schwarzenberg was born in 1463 as the son of a knight. He therefore underwent the usual training to become a knight: he learned to ride and to break the lance, and was educated in courtly behaviour. He entered his first tournament at the age of 14. Meanwhile, his education in reading, writing and arithmetic was neglected.

Johann of Schwarzenberg shared the fate of many imperial knights: his family’s assets were not enough to finance a life befitting his social status. So, he looked for work. Military service proved to be unprofitable for him. Fortunately, however, the Bishop of Bamberg entrusted him with the administration of his property in 1499. This meant that an illiterate man was at the head of the administration of one of the most powerful territories in the empire. This could have led to disaster had Johann of Schwarzenberg not known how to acquire the knowledge he needed for his work: but he brought in scholars who had studied at universities, and applied their theoretical knowledge in practice. His first great achievement was his new Halsgerichtsordnung (‘procedure for the judgment of capital crimes’) of Bamberg. In it, he combined local customary law with the legal concepts of the universities. This was so innovative that Emperor Charles V asked him to collaborate on the empire’s first generally applicable criminal law. Thus, the drafts of an illiterate man became the basis of German criminal law.

Cicero, De Officiis: A Crash Course For The Illiterate

Johann of Schwarzenberg wrote his book for his fellow nobles in order to provide them with the knowledge they needed to earn a living as councillors at a princely court. In doing so, he had to overcome the problem that most knights did not speak Latin and could barely read. As the basis for his work, Johann of Schwarzenberg chose a book that was considered a textbook on political governance during its time: Cicero’s De Officiis, which translates as ‘On Duties’. Written in the second half of 44 BC, it outlined the rules that a politician should follow in order to be successful.

Cicero had claimed to have written it for his son, which is why Johann of Schwarzenberg chose the following title for his book (translated): A book that the Roman Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote for his son Marcus on well-administered offices and the qualities of a good and honourable man, written in Latin, translated into German at the request of Herr Johann von Schwarzenberg and then adapted by him into artful High German, with many pictures and German rhymes for general use in print.

Johann of Schwarzenberg thus describes the highly complex process of creating the text, as his peers would not have known what to do with a simple translation. He had the Latin text paraphrased for them. He edited this translation to make it more comprehensible. He left out what he considered too complicated. Where an explanation was necessary, he added it. Finally, a humanist ensured that the essential content of the original text was preserved.

To emphasize the central messages, Johann of Schwarzenberg had them illustrated according to his specifications and composed catchy verses that were easy to memorize. This page answers the question of what a military measure should look like: appropriate, neither too timid nor exaggerated. As an illustration, he chooses a ship that has run aground, which the merchant is refloating by throwing some of his goods overboard.

Johann of Schwarzenberg discusses the new ideal of thrift several times. This illustration shows how excessive generosity ruins the knight. Not everyone could afford donations to the poor, banquets, tournaments and hunts. For this reason, Johann of Schwarzenberg expresses in his rhyming verse that moderation is essential. This is exemplified by an illustration of the head of the household refusing his family’s requests for more money.

Johann of Schwarzenberg also addresses moral ideas. Here, he calls on his readers to compete fairly.

Some of these ideas still shape our understanding of the law today. Johann of Schwarzenberg described what the Swiss Criminal Code now defines under Art. 128 as ‘Failure to offer aid in an emergency’ as follows: ‘If one murders and the other tolerates it, both are equally guilty.’

3.2 - University Education Under the Sign of the Confessionalization

The Influence of Religious Dispute On Education

The Protestant princes who seized possession of the church were faced with a problem: all services previously financed by the church were no longer available. These not only included care for the sick and the poor, but above all education. However, since the early modern states were dependent on well-educated administrative officials, the Protestant sovereigns founded their own schools. The Catholic side, namely the Jesuits, followed suit and developed the most progressive primary school system of the time, on which our school system is still based today. For the first time, the Jesuits divided their pupils into grades. Only those who passed their exams at the end of the school year were allowed to move on to the next grade. Fixed learning content and textbooks made education somewhat less dependent on the teachers’ abilities.

The competition between Protestants and Catholics thus triggered a school reform and provided the young territorial states with excellently trained civil servants who contributed to the professionalization of administration throughout the empire.

Philipp Melanchthon and the Protestant School System

Philipp Melanchthon, humanist and reformer, was among those who had a lasting influence on the Protestant school system. He came from a middle-class background. His father had the financial means to send him to the Latin school in Pforzheim. The transition between Latin school and university was very fluid at the time, which meant that Melanchthon not only learned Latin at school, but also Greek. During his studies in Heidelberg and Tübingen, he also learned Hebrew. This was not unusual. Until the 19th century, school education focused heavily on the area of languages.

In 1518, Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony appointed the 23-year-old as Professor of Greek at the University of Wittenberg, where a certain Luther had publicly presented his theses the previous year. Luther and Melanchthon would go on to become the dream team of the Reformation.

Melanchthon not only systematized Luther’s sometimes contradictory writings; he also developed a new educational system, which formed the basis for numerous Latin schools, as well as the school regulations of the Electorate of Saxony from 1528. These regulations were understood to cover the entire content and practical organization of school education, ranging from a rough outline of learning content and timetable to the qualifications and salaries of teachers.

Euclid: The Most Important Textbook On Mathematics

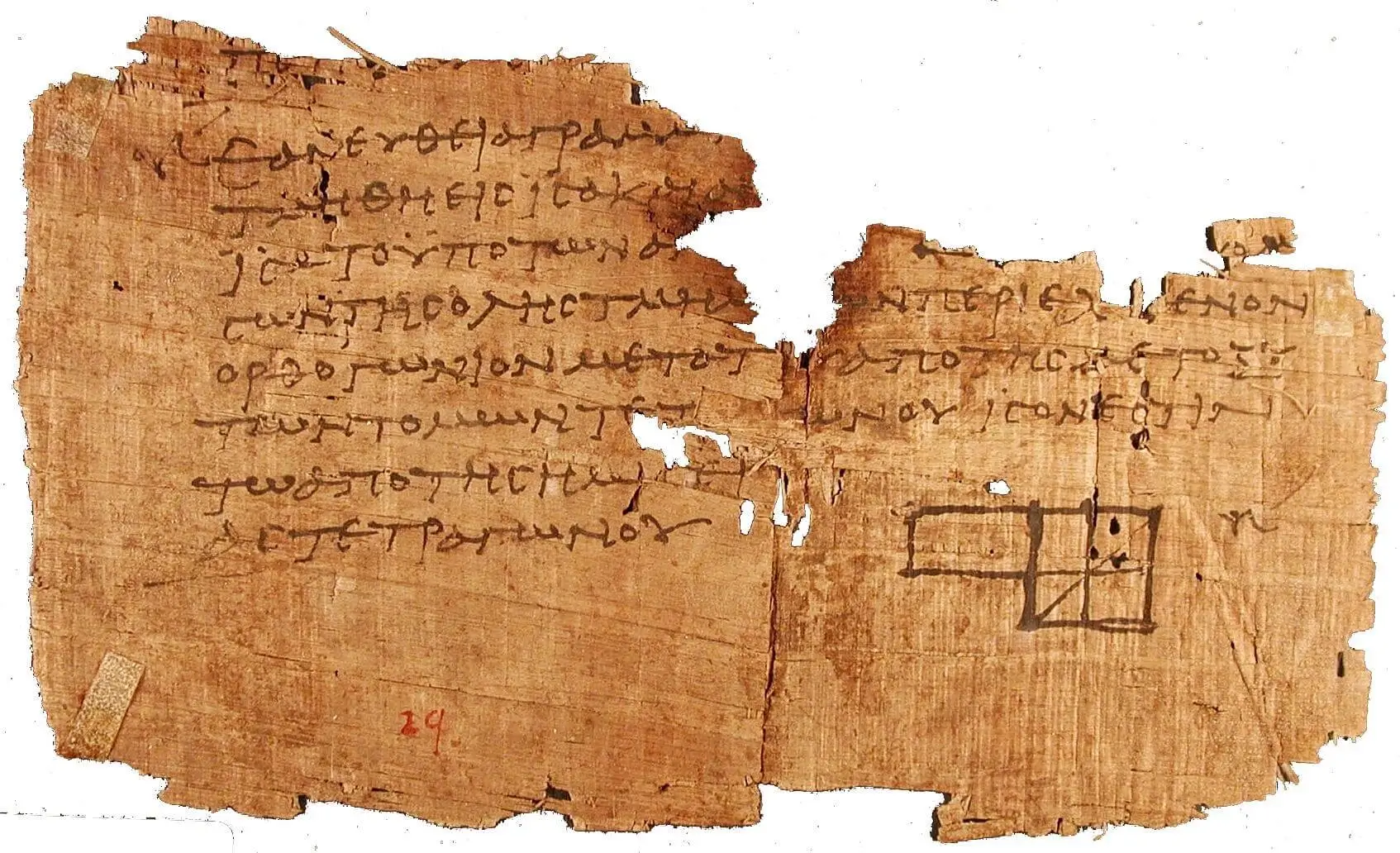

Mathematics remained one of the few generally recognized subjects. It was accorded special level of importance. After all, everyone needed it: theologians to calculate the date of Easter; builders and artists to coordinate proportions; generals to prepare for the logistics of war. Whether a nobleman wanted to check a merchant’s invoice or his tax collector’s account book, he had to be able to calculate. Euclid’s Elements was considered the most important textbook on mathematics.

The edition shown here was produced in Basel in 1537 and published by Johann Herwegen. It contains not only Euclid’s Elements, but also his Optics and other short writings.

Philip Melanchthon provided the foreword, in which he recommends that the book be read by ‘adolescent students’. The fact that the foreword was written by a Protestant theologian meant that the work did not sell in Catholic areas. For this reason, the next edition did not include Melanchthon’s foreword.

Melanchthon was a great promoter of mathematics. He suggested appointing a second mathematician at the University of Wittenberg. For the first time at a German-speaking university, he separated the subject into lower- and higher-level mathematics.

The reason for this was the Protestants’ desire to catch up with the Catholics in the field of astronomy, the study of which was closely linked to mathematics. Later, they even tried to bring Johannes Kepler to Wittenberg, but he refused the appointment.

By the way, Euclid was not from Megara, as stated on the title page of this book. Since the ancient literature only mentions one Euclid from Megara, it was automatically assumed in the 16th century that he had written the Elements. Today we know that this is not the case. The Elements were written by a Euclid who worked and taught at the Mouseion of Alexandria.

Station 4 - Education, The Perfect Man and Paradise On Earth

During the 18th century, the bourgeoisie rose to power. Their philosophy revolved around the Enlightenment. Here, the focus was on man, who was believed to be able to create his own paradise on earth, without divine commandments or supernatural assistance. The condition: each individual had to devote all their efforts to the realization of the Good.

Unfortunately, reality did not live up to the hopes of the Enlightenment philosophers. People remained selfish and attached to their habits. The intellectual ruling class saw only one way of combatting this behaviour: education from an early age. Education was no longer understood in the sense of vocational training. Instead, it was defined as the shaping of character according to contemporary ideals in the name of reason. It was expected that one who successfully completed this education would become a well-adjusted citizen who behaved in line with the interests of the state.

In the first part of this station, we will introduce you to the work that popularized this idea of education. Its title in English is Émile, or On Education. It was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau from Geneva.

The second part focuses on how this new education was taught in practice in the 19th century. We’ll follow the pupils of a Geneva boarding school as they zigzag across the Alps.

4.1 - Education Is More Than Imparting Knowledge

Reason as the Basis of the Common Good

Those who strive for a democracy in which all state and religious pressure is minimized need other mechanisms to motivate people to serve the community. All the unwritten norms and ideals that a child is taught during their many years of education are an excellent means of doing this.

In his book Émile, or On Education, Jean Jacques Rousseau took a stand against the – in his view – misguided pedagogy of absolutism. He argued that the standards of education in force at the time did not exploit all of the child’s potential to become a happy citizen who will represent the interests of the state. He believed it was necessary to abandon the old norms and focus instead on what he called the natural development of the child. In doing so, he relied on the child’s reason. The child would make sensible decisions of its own accord.

Even today, it is occasionally overlooked that what Rousseau considered to be ‘natural’ and ‘reasonable’ was and is reflective of the time in which he was living. The education promoted by Rousseau conveys norms that are neither ‘natural’ nor ‘reasonable’, but are taught until the child perceives them as ‘natural’ and ‘reasonable’.

The Self-Education of Jean Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau was born in Geneva in 1712 as the son of a watchmaker. Geneva was one of the areas that already had compulsory education. Rousseau is therefore likely to have learned toread in a state elementary school. His father encouraged the child’s love of reading, but in 1722 he had to flee from prosecution. The family sent the 10-year-old Jean-Jacques to board with a pastor before he began his apprenticeship with an engraver at the age of 13. At 16, Rousseau left his master to embark on a kind of wandering journey. He was self-taught for more than a decade before he was accepted among the Parisian intellectuals.

In 1749, the Academy of Dijon offered a prize for the answer to the following question: ‘Has the revival of the arts and sciences contributed to the purification of morals?’ In his essay, Rousseau denied this and claimed that man is only free and independent in the ‘state of nature’. With this thesis, Rousseau not only won the prize money, but also the attention of the public. He became a thinker whose books were passionately discussed throughout Europe.

On Education

His best-known work to this day is the novel Émile, or On Education, published in 1762. It was translated into German in the same year and into English one year later. By the end of the 18th century, the bestseller had appeared in a total of 59 French and 21 foreign-language editions. Even today, Émile is still considered specialist educational literature.

In Émile, Rousseau describes how an empathetic pedagogue can educate a young man of average talent to become a functioning and happy citizen. The work was highly controversial, not so much because of its pedagogical ideas, but because of an insertion in Book 4. In it, a ‘Savoyard Vicar’ opposes all revealed religion and calls for a “natural” religion instead. This passage prompted the Parisian parliament to ban Émile and issue an arrest warrant for its author. The government of Geneva also condemned the work.

Contemporary Enlightenment thinkers, on the other hand, were enthusiastic about this digression, while they were rather indifferent to the rest of the book. It only came to prominence after the French Revolution, when parliament began discussing a new school system and many members of parliament quoted Rousseau.

Book 1: The Infant (0-5)

Rousseau describes Émile’s upbringing chronologically, following him through the different ages. He begins with the infant, whom he believes should be breastfed by a loving mother. The infant should grow up in as natural an environment as possible. There, it learns to speak by imitation without additional training.

The Boy (5-12)

When the boy is five years old, the actual lessons begin. The focus is not on memorization, but on personal experience. The child learns through direct encounters with nature. If he commits a deliberate act of wickedness, he is not punished, but he has to live with the consequences: if he destroys a window pane, for example, it will not be replaced, leaving the child freezing in the night, regretting his deed.

The Adolescent (12-15)

Rousseau assumes that by the age of 12, the boy has a well-established personality, and is ready to be taught the most important learning content over the following three years. The focus here is on the natural sciences. The boy observes phenomena and seeks explanations with the help of his teacher. This trains his independent thinking. Manual skills are also important. This is why the child is only allowed to read one book, Robinson Crusoe. This character is regarded as the archetype of homo faber, who builds a civilization even in the deepest wilderness.

Puberty (15-20)

The last phase of education deals with puberty. The teacher’s task is to ‘sublime’ the student’s emerging feelings and steer them in the right direction. Émile is to become a young man who controls his sexual desires and develops them in accordance with his parents’ wishes. He should not accept the bride intended for him, but yearn for her.

This bride – Rousseau calls her Sophie – was raised as a companion for Émile. She will “submit” to him and be “useful” to him. This reflects the Enlightenment’s perception of women, which sees men as the superior sex, while denying women any cognitive abilities.

There are many of Rousseau’s ideas that one could criticise. Even his contemporaries did so. They accused him of not having applied his theory in practice. After all, it was known that he had abandoned the five illegitimate children born to him by the washerwoman Thérèse Levassur in an orphanage.

4.2 - State School Versus Progressive Education

The Right Way To Think

Industrialization required educated workers. Business owners demanded that the state implement compulsory education and align the curriculums of grammar schools and universities with the skills that were needed in the factories. This demand still persists today. Companies consider it a key locational advantage to be able to draw on a highly trained workforce. From their perspective, it is the task of the education system to turn every pupil into a perfectly moulded cog that keeps the well-oiled machine of the national economy running. This demand meets with little protest because it also offers benefits for wage- earners: a better education means a higher salary.

This work-oriented style of education contrasts with the wishes of many parents. They want to offer their child an education that serves their individual development. To this end, they are happy to pay high fees for private schools and boarding schools, where various forms of progressive education are practised. This development also began in the 19th century. One of the earliest progressive boarding schools was run by Rodolphe Töpffer in Geneva.

Rodolphe Töpffer’s Boarding School

Rodolphe Töpffer, born in Geneva on 12 pluviôse of the VIIth year (= 1799), was a child of the French Revolution. His father was a successful artist who socialized with many intellectuals. This environment provided his son Rodolphe, who probably attended the state school in Geneva, with plenty of inspiration. Rodolphe would have liked to become an artist himself, but an eye condition forced the young man to change his mind. He became a teacher and used his wife’s dowry to found his own boarding school for boys in Geneva in 1824. His school became famous for the hikes that Töpffer took with his pupils, which often lasted several weeks. Inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he taught his pupils basic knowledge of nature, history and geography. The whole of Europe knew about this because Töpffer published illustrated reports that were extremely popular. Today they are considered forerunners of the comic strip.

Voyages En Zigzag

Originally, the drawings for the Voyages En Zigzag were intended for internal use. Töpffer created albums that he could use, once he had returned home, to consolidate what he had learned on the journeys and pass it on to other students. From 1832 onwards, he sold autographed albums of every journey. They became bestsellers, so much so that a Parisian publisher asked him if he would like to turn them into a book. The Voyages En Zigzag were so successful that several editions were produced and a second volume was published.

During the Voyages En Zigzag, every encounter with nature served to educate the pupils, whether they were finding snakes under stones or catching butterflies with their hats.

Of course, the young travellers also visited the big sights during their hike, which served as a vehicle by which to give a history lesson.

The Arch of Augustus in Aosta must have provided the perfect backdrop for a lesson on the Roman Empire.

On this page, Töpffer pointedly illustrates the difference between dead book knowledge and what his boys learn on their journey.

This illustration addresses the same idea again.

Töpffer believed it was very important that fun was not neglected during the hikes. For him, laughter was part of education.

Training Or Education: The Crucial Question

What should the aim of schools, universities, academies and other educational programs be? Should they be preparing us to survive in a highly complex environment? Or should they be striving to produce the ideal human being who is enlightened, self-determined and responsible for changing the fate of the world for the better?

Are we treating education as the means of our salvation?

And, by doing so, are we challenging our education system, or asking too much from it?